A New Light

Originally slated for the landfill, street lamps that have illuminated Montréal’s streets since the ‘60’s are getting a second life.

Photos courtesy of Studio Botté

MONTRÉAL’s CLASSIC STREET lamps are being modernized, replaced individually with LED bulbs, rendering the familiar glowing glass orbs obsolete. But with the help of a local artisan, who came across the discarded lamps, some will see a new life instead of going to the landfill.

Philippe Charlebois Gomez, the founder of studio botté, remembers the day a friend sent him a quick photo of the globes on the side of the street. This is a typical process of material collection for Charlebois Gomez, who upcycles discarded items like fans (more than 3,000 in the past five years), blinds and broom poles found around Montréal into high-end light fixtures.

Charlebois Gomez hustled to pick up the spheres. “I realized when I had them here at the studio, that they were the street lamps from the City of Montréal, dating from [the time of] Expo 67, and I was in disbelief,” he says.

Now, the plan is to turn these artifacts of local history into light fixtures—potentially even engraving them with the names of streets they spent years shining light on—in a project called Faro.

Throughout their decades of use, the lamps aged and discoloured differently, depending on their sun exposure. “Some of them were sprayed with black paint on half of the sphere because people didn’t like the light coming in through their bedroom window,” Charlebois Gomez says.

He later learned that between 4,000 and 12,000 lamps would be thrown out in total, part of a larger city-wide effort to convert all street lamps to LED. “That’s when I went, ‘Oh my god, this is bigger than me,’” he says.

The more than 140 lamps he has collected so far (with the help of a local upcycling organization) will have to be cleaned out, sanded down and wired. The project will be the largest he has taken on so far and the first in which he will have others working on the light fixtures with him.

“I’m used to tackling every one of my lamps myself from start to finish,” he says.

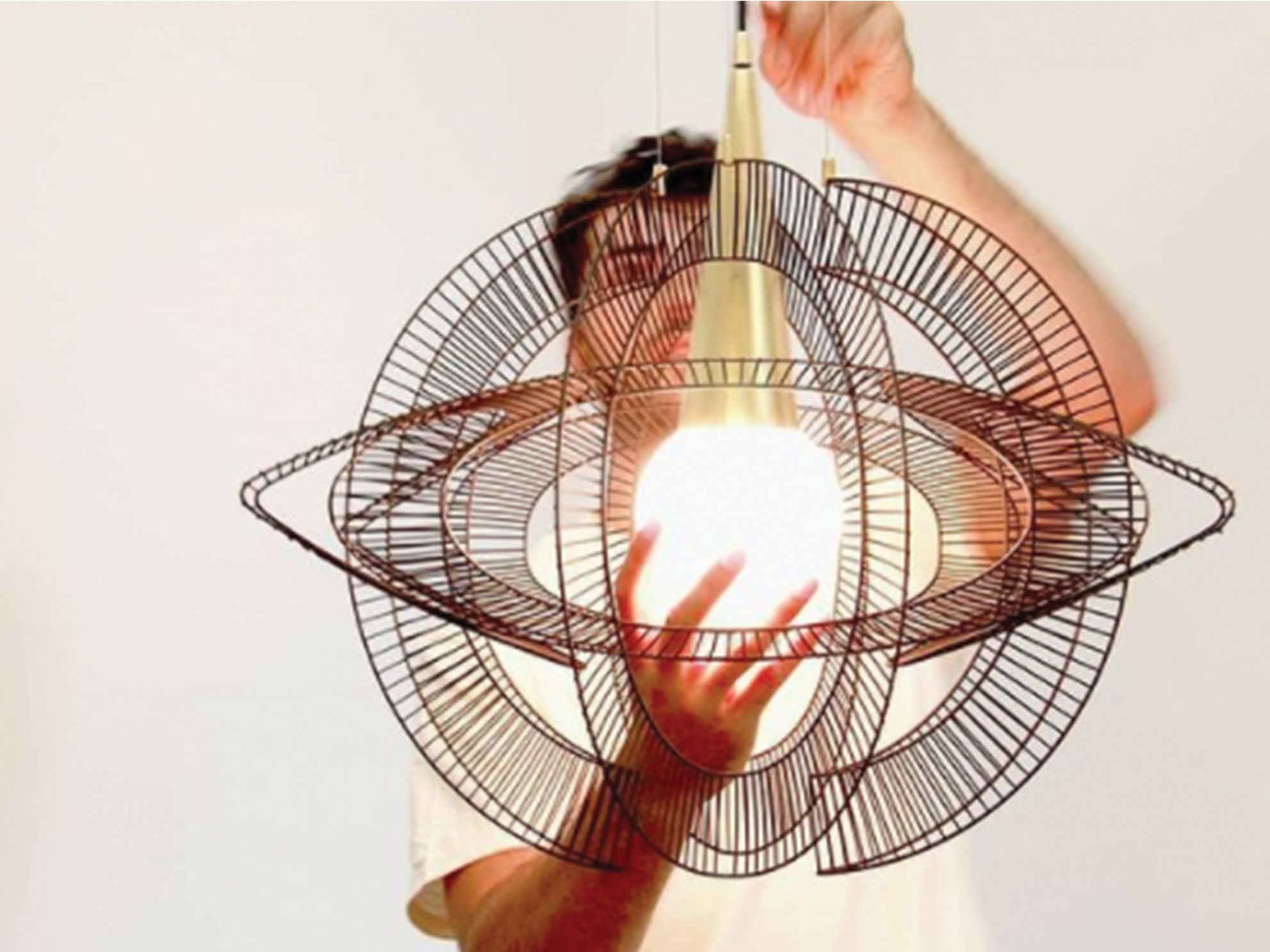

Philippe Charlebois Gomez says fans are commonly discarded because they’re heavily used during Montréal’s summers, but aren’t worth fixing to most.

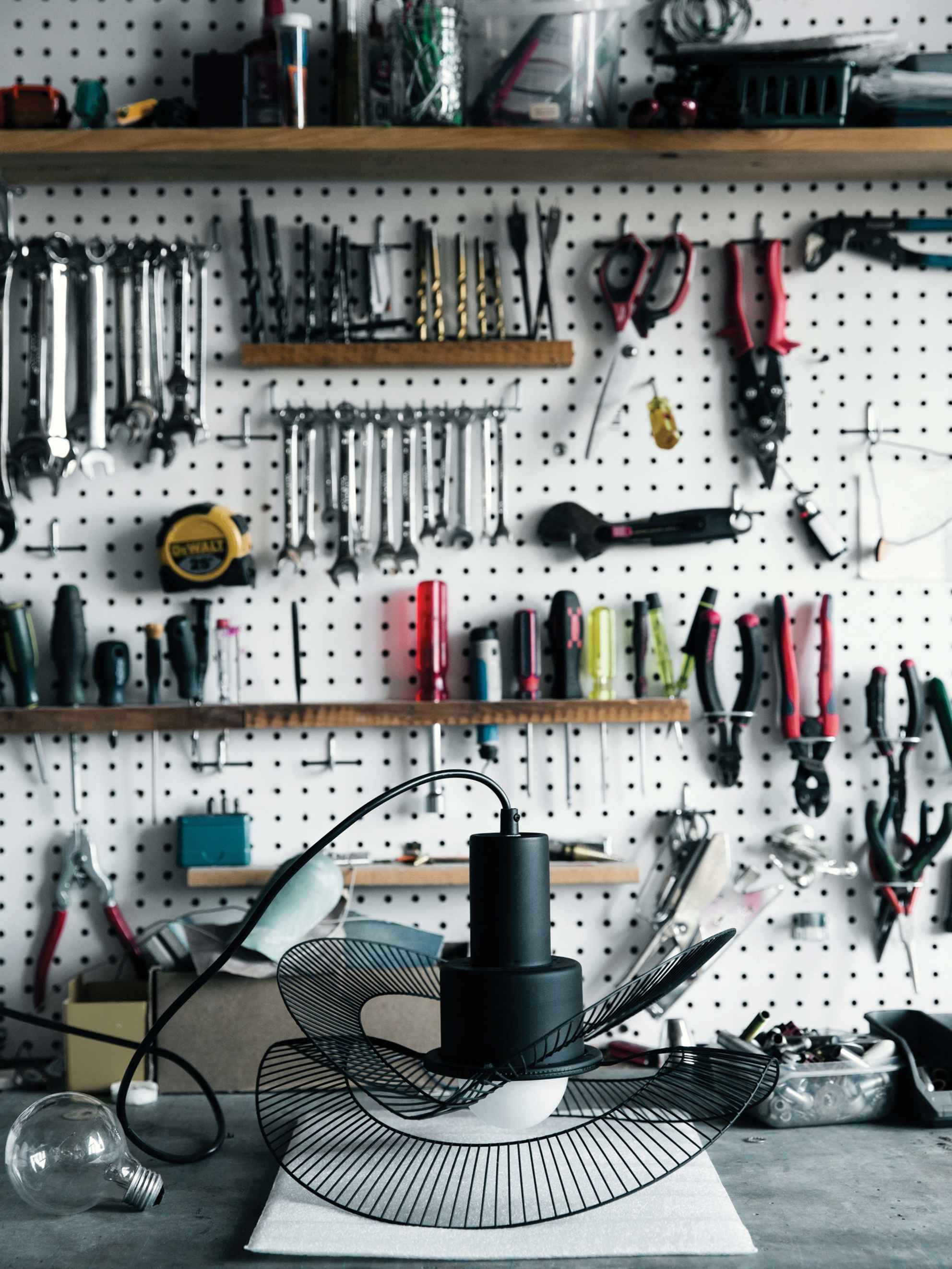

Charlebois Gomez’s first upcycled lights were made from fans, with a coat of paint—one of the last steps in the process—bringing them back to life; the PDP series of lights, made from old blinds, is a top seller for the studio; scavenged fan guards are stored on rods in the studio until put to use; a carefully balanced prototype of the Faro lamps.

Charlebois Gomez hypothesizes that each city has a different selection of commonly discarded items; Charlebois Gomez installing a light fixture made from discarded fans, some of which have been bent into new shapes; a bike, the original collection vehicle; old lamps and light fixtures are displayed on shelves in clear view, so Charlebois Gomez can keep them in mind as inspiration. Photos by Marjorie Guindon

Charlebois Gomez started studio botté about four years ago, after quitting his job in industrial design. The artist credits his creativity and interest in upcycling in part to his mother, who ran crafting workshops using recycled materials at orphanages and schools where he’d help out.

“I think it really sharpened that muscle in the brain that tells you that any material can be malleable and transformed,” he says.

Then, while working in design, he started collecting fans and other discarded items around Montréal on his bike commutes, storing them under his desk without knowing how he would put them to use.

“People throw out anything that seems to be a little broken,” he says. “I realized there’s so much material that isn’t being tapped into.”

Over time, Charlebois Gomez’s scavenged materials took over the 1,800-square-foot studio he shared with three roommates, which is now studio botté’s showroom, workshop and stockroom.

Studio botté’s fixtures, like this one called Cilla, have a high-end look, which Charlebois Gomez says doesn’t fit what most people expect from upcycled items.

Véronique Grenier, Charlebois Gomez’s girlfriend, who has been involved with the studio since its inception, says she remembers how the collected materials gradually took over each room of the apartment. “When it came to the last room, which was my home office and a storage space at the time, that was when we decided it was time to move out and let the studio take over the whole space,” she says.

Charlebois Gomez says he doesn’t have much time to scavenge for materials by bike anymore, but he has about a dozen friends on the lookout for him, all across the city.

“Like everyone who knows Philippe and what he does, I can’t help but pick through trash on the streets while taking a walk or riding around on my bike,” Grenier says. “When I see a fan just lying there on the curb, I get this little jolt of excitement.”

Despite the studio’s growth, Charlebois Gomez says that relying on scavenged materials, crafting each piece by himself and only shipping the pieces locally has kept the operation on the smaller side—the way he wants it.

“I’ve been sort of phobic to growing my company, having seen what can become of a small artisanal place when it turns into a much bigger one,” he says. For Charlebois Gomez, small is sustainable.