Pang print shop in limbo as artists decry lack of funding

Jolly Atagoyuk and Andrew Qappik say they want to be in the studio working on a print collection

Jolly Atagoyuk sits at his old worktable at the Uqqurmiut print shop in Pangnirtung, reminiscing on past print collections he’s worked on. (Photo by Mélanie Ritchot)

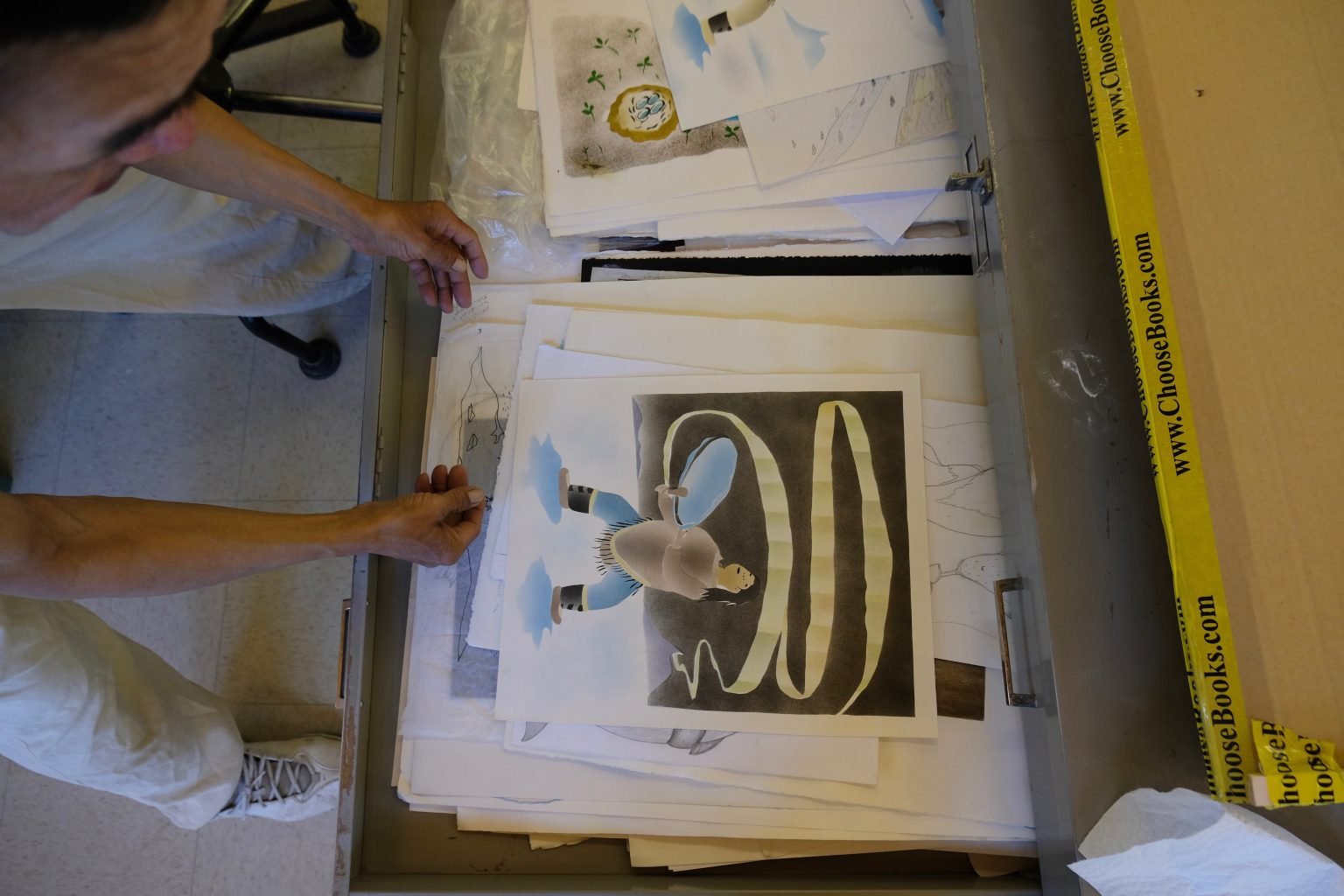

JOLLY ATAGOYUK, a printmaker from Pangnirtung, opens shallow wooden drawers — one by one — and sifts through dozens of his sketches and prints from years past.

Around him in the hamlet’s print shop, a space once occupied by nine or so artists, are work tables are scattered with old supplies, partially finished prints and storage boxes — all seemingly frozen in time.

Atagoyuk is part of a group of renowned printmakers from Pangnirtung decrying a lack of funding he says keeps them from producing art like they once did.

The community’s print shop, located in the Uqqurmiut Arts & Crafts Centre, opened in 1969 as part of the federal government’s efforts to create jobs in the community.

Operating on federal and territorial funds, Pangnirtung artists released annual print collections for many years, creating a relatively consistent income. Some of the artwork created at the shop has been exhibited in the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Now, financial documents obtained through Nunavut’s access to information law show more money coming into Uqqurmiut Arts & Crafts Centre than ever, while the community’s former artistic hub is hardly being used.

And nobody seems to know why.

“We used to all come here every day and work,” Atagoyuk said.

“We keep waiting for funding … we just keep waiting.”

Jolly Atagoyuk sorts through drawers of prints and sketches he’s done over the last twenty years. (Photo by Mélanie Ritchot)

Atagoyuk said he and other printmakers haven’t been given money to start on a new collection of prints since 2018. The artists involved with the centre received about $66,800 between them that year, according to the financial documents.

Some artists still go to the studio occasionally to make prints on their own, some of which are for sale in the gift shop adjacent to the print shop. In 2020, the artists received about $8,800 in print sales, the smallest amount in at least a decade.

To keep money coming in, Atagoyuk makes mini prints from his home and sells them around town.

“That’s all I can make,” he said of the prints, which are no larger than a postcard.

Meanwhile, Uqqurmiut Arts and Crafts Ltd. had its biggest surplus in at least 10 years at the end of the 2021 fiscal year — more than $380,000 in the bank.

The Uqqurmiut Arts & Crafts Centre was initially owned by the Uqqurmiut Inuit Artists Association and was run by a council of Inuit artists. Now, the Nunavut Development Corp. is its main funder.

It contributes about $238,000 in operating funds to the centre yearly, including both the tapestry studio and print shop that make up the Uqqurmiut Arts & Crafts Centre, according to financial documents.

In 2014, a Canada Post branch was built in the back end of the studio. Since then, Uqqurmiut Arts & Crafts Ltd. has made $350,117 from the venture, according to the financial documents.

In 2019, a small Royal Bank of Canada branch was added, taking up even more of the space. The same documents show the centre began turning a profit with the RBC branch in 2021, when it brought in just under $8,000.

Atagoyuk said printmakers agreed to let the two agencies move in, believing they’d see revenue come back to the print shop.

“That’s what we were told,” he said.

Jolly Atagoyuk, Andrew Qappik and other artists are seen in a photo taken around the time when the print shop first started up in Pangnirtung, in 1969. (Photo by Mélanie Ritchot)

The Nunavut Development Corp. money should be flowing down to the print shop, said Andrew Qappik, a renowned printmaker and member of the Order of Canada involved with the print shop since its inception. But, he said, he hasn’t seen the print shop funded for at least three years.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” Qappik said.

He said he and other artists have discussed seeking private investors to fund a collection — a backup plan he said the group discussed in case the print shop ever got in trouble.

Goretti Kakuktinniq, business adviser of cultural industries at Nunavut Development Corp., said in an email the COVID-19 pandemic and short staffing have created challenges for running the print shop.

Uqqurmiut manager Elena Akpalialuk has been in charge of running multiple agencies in the building — the RBC and Canada Post branches, as well as staffing them, Kakuktinniq said.

Akpalialuk, who was unavailable to comment for this story, is also in charge of both the print shop and tapestry studio.

“It’s been a great struggle for her, and we were unable to look at having a print workshop for a few years,” said Kakuktinniq.

Recently, an assistant was hired to help Akpalialuk manage the large workload, and the centre is applying for money to do a weaving and print collaboration with the print shop in Ulukhaktok, N.W.T.

As well, with fewer tourists passing through the community due to COVID-19, Kakuktinniq said the development corp. has been purchasing prints from the artists.

“This is the time we need to support the artist in the community,” she said.

Andrew Qappik’s worktable at the Uqqurmiut print shop is in a back corner, covered with supplies that hinted he was recently working on a print, fellow printmaker Jolly Atagoyuk said in the summertime. (Photo by Mélanie Ritchot)

Paul Machnik, a printmaker based in Montreal, has worked with Pangnirtung artists, including Qappik and Atagoyuk, and has been involved with other print studios in Nunavut and Nunavik.

“It’s a huge undertaking,” Machnik said of the work needed to release a print collection.

“To leave that to one manager, to get the word out for both tapestries and prints, to go after funding, keep track of things on the ground with the artists, and then promote the work, it’s too much for just one person.”

For the Pangnirtung printmakers, some lobbying might be needed, he said.

“There has to be a group effort on the ground by the artist to say, ‘We need this, we want to do this.’”

Of the state of the print shop, Machnik said: “It is difficult to watch, but it is repairable.”